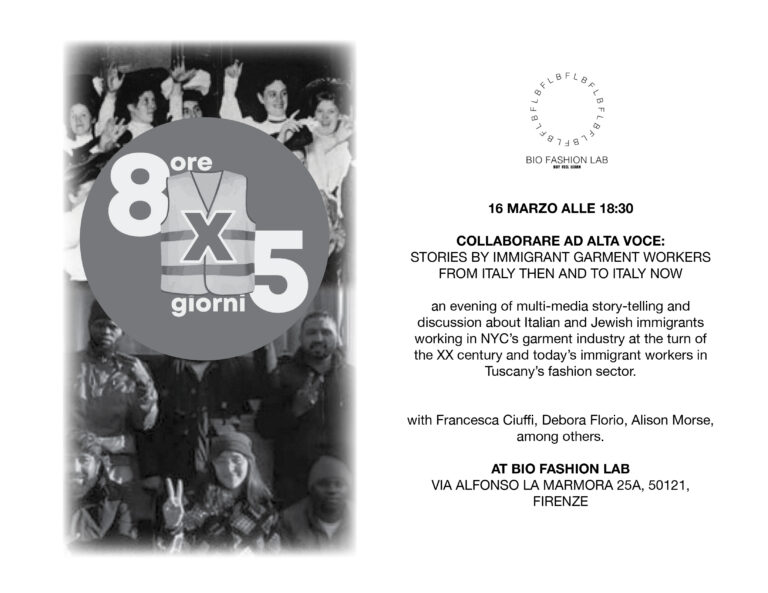

“Collaborare ad Alta Voce: Stories by Immigrant Garment Workers From Italy then and to Italy Now,” was an evening of multi-media story-telling and discussion about Italian and Jewish immigrants working in NYC’s garment industry at the turn of the XX century and today’s immigrant workers in Tuscany’s fashion sector.

With Francesca Ciuffi, Maria Grazie Cotugno, Giulia Falzoi, Debora Florio, Alison Morse, Raza Muhammed, Claudio Tosi and Abbas Zaigham

Organized by Alison Morse

March 16 at 6:30 pm at Bio Fashion Lab, Via Alfonso La Marmora 25A 50121, Firenze

Audience at Bio Fashion Lab

Alison reading her poetry

Debora talking to the audience

Abbas, Raza and Francesca respond to an audience question after Abbas and Gaza told stories in Italian of their struggles for fair pay and decent work hours in the Tuscan leather factory where they work — a factory making products for an international luxury brand — and the support they receive from the 8X5 Movement in Prato. Francesca, from the 8X5 Movement, translated their stories into English.